Counterfeit cases: fakes and forgeries in Antique Silver

The quarterly meetings of the Goldsmiths’ Hallmark Authentication Committee (known as the Antique Plate Committee when this article was first published) are usually concerned with mundane items such as tankards converted into hot water jugs, re-shaped dinner plates and rose bowls constructed from meat-dish covers. However, just occasionally a group of pieces is brought to the Committee’s attention which gives real cause for concern. Sometimes these pieces would be of very high value if they were genuine, but more often than not it is a large volume of relatively low value pieces which presents the most problems - For this class of silver, 2008 was truly a bumper year.

In early May 2008, a dealer alerted two members of the Committee to a collection of over 120 bosun’s calls, the whistles with which the Clerk and the Assistant Clerk of the time were wont to be piped aboard during their earlier careers. Now three or four of these together might be considered normal, but such a large group was truly exceptional. The collection had, according to the auctioneers’ introduction, been formed on the advice of a ‘knowledgeable elderly antiquarian, who haunted the antique shops in the Lanes (sic) of Brighton, in London and other likely sources, where he snapped up all the calls on offer’. Perhaps the combination of ‘elderly’ and ‘snapped up’ should have alerted all but the most insouciant. The two Committee members examined the collection independently, under the baleful eyes of the auction room staff, and found that they had problems with about 50 of the 88 calls bearing hallmarks from London, Birmingham, Dublin and Edinburgh, and silversmiths’ marks for Inverness and Dundee. One call was improbably early (bearing hallmarks for 1671); two bore the marks of Paul Storr (not a name immediately associated with whistles); and several bore the marks of the Bateman family. Other calls had the marks of well-known flatware specialists and at least one had the little additional mark of the workman (or journeyman) which identified the actual maker of a piece of flatware rather than the workshop. This proved to be the key. The greater number of the hallmarks appeared to have been cut from silver (or gold) dessert knives, which formed the ‘keel’ of the whistle. There were also several European calls which had been similarly constructed.

After a spirited exchange of emails between the auction house and the Deputy Warden of the Assay Office, the sale was cancelled and all the calls were sent to the Hall for examination. Thankfully for those involved, the metal tests undertaken by the London Assay Office confirmed the views of the two members of the Antique Plate Committee: that the flat ‘keel’ was of the date of the hallmarks, but the ‘gun’ and the ‘buoy’ of the whistles were of modern metal. The owner now has a somewhat smaller collection of British calls which appears to be genuine, even if the same cannot be said of his continental silver examples, or those made in base metals.

The saga of these calls highlights the dangers of buyingz in an area where one has little knowledge. Much more dangerous is the current practice of buying online without even viewing a piece. Selling through online auctions was the preferred method of disposal of another, and well-known, forger. In one of the largest cases of English silver forgery of its kind, the Antique Plate Committee, the London Assay Office and the Metropolitan Police, successfully brought Peter Ashley-Russell to justice at Snaresbrook Crown Court on 26 September 2008. One hopes that such appearances are not becoming something of a habit for Ashley-Russell who had his collar felt in 1986, following the sale of a gold spoon and fork, purporting to be seventeenth-century, through a London auction house in July the previous year. On that occasion, when several other pieces of flatware were also proven to be of his manufacture, he was detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure for 21 months.

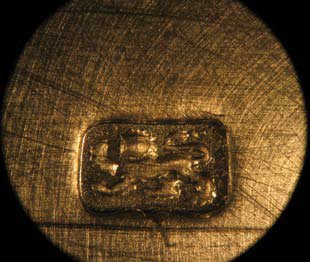

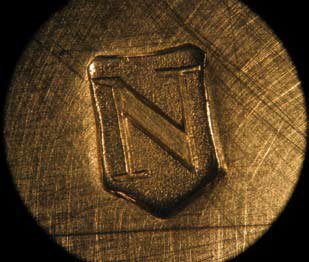

The story of his current conviction goes back as early as 2002 when a group of marrow scoops and trefid-end spoons was submitted to the Antique Plate Committee by two auction houses and a West Country dealer. In 2007 the police raided Ashley-Russell’s house and found, in his workshop, a large quantity of silver, mainly flatware but also coffee pots and a tumbler cup, and, crucially, 53 punches bearing false hallmarks. However, it soon became evident that the forger had altered his approach to faking by specialising not only in the manufacture of spurious spoons, which he clearly still did, but also by altering old spoons into much more valuable forks and by applying false marks to genuine pieces with worn marks and re-patinating the pieces to age them.

The punches discovered at his premises were of extremely high quality and the act that they were forgeries would not have been detectable from a photograph on the internet. Although the police had neither the time nor the money to investigate Peter Ashley-Russell’s internet auction accounts, it is estimated that he produced something in the region of 450 pieces before his arrest and subsequent sentencing to three years’ imprisonment under the 2006 Forgery Act. His is the most significant prosecution for hallmarking offences since the 1890s when the Goldsmiths’ Company was instrumental in convicting Reuben Lyon and Charles Twinam for similar crimes. As it did in that case, the Company has published, a comprehensive list of all the marks found in Peter Ashley-Russell’s possession in order to assist in the detection of pieces already in the public domain.

What is curious about these cases is the relatively low cost of the items being faked. The bosun’s calls carried pre-sale estimates of around £200, although the ‘early’ and ‘rare’ pieces attracted higher sums. At Mr Ashley-Russell’s trial, the expert witness for the prosecution estimated the total value of the 39 exhibits at £20,000. This is a far cry from the £90,000 bid for a spurious sugar bowl and cover, with a matching cream jug, at a West Country auction house in 2002 which also proved to be of modern manufacture, but by another silversmith. Perhaps the makers of the calls, and Mr Ashley-Russell, judged that the low value would be an advantage in escaping detection, but neither had reckoned with the Antique Plate Committee and the expertise of the London Assay Office.

Written by Charles Truman | This article was originally published in the 2008-2009 Goldsmiths’ Review.